For those who would like to swot up a bit for the Unit 1 exam:

♦General revision handout

♦Buzz words handout with sample questions

Of course, there are some Kahoots below that might help you to hone your multiple choice skills:

I am by no means sure that I can justify the use of Kahoots in my classroom. They are too much fun and students don’t even moan when I say, “We’re having a Kahoot today”. Instead, they make up ever more absurd nicknames for themselves and groan or cheer their way through my questions. Surely Kahoots can’t be educational.

Fortunately there is an option for students to complete Kahoots at home alone, which significantly reduces their entertainment value. By providing my Kahoots here, I can deceive myself that all that reading of multiple choice questions, whether in the company of others or alone, will benefit my students in the long, frenetic lead-up to the VCE exams.

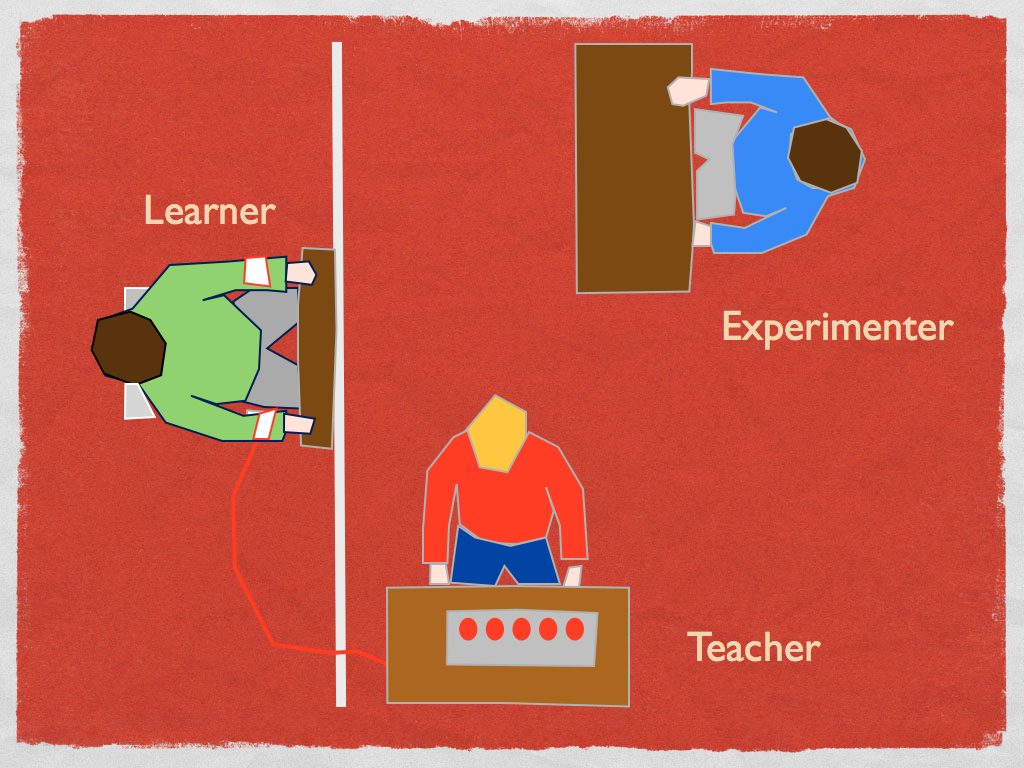

By using the “Preview” version, a student can play a Kahoot on one device. The simulated smartphone shown on the screen is the mode provided for inputting answers.

In case other psychology teachers find this post and would like to use my Kahoots for their students, I am also providing links for the classroom versions of each one.

•If playing alone, create a free account at this link: https://getkahoot.com/ .

•Alternatively, if playing in class, each student needs to go to http://kahoot.it/ to enter the game pin.

Psychology 1 – Buzz Words

•Play alone with the PREVIEW version

•Play in class with the normal version

Download: PDF of questions and answers

Development and the Human Lifespan

Please note: I was hamstrung in writing these questions by the limitations in length allowed by the Kahoot website. Therefore some are not as elegantly and precisely expressed as I would have liked. The Kahoot website kept truncating my flowery prose. In any case, that’s my excuse for any substandard expression.

•Play alone with the PREVIEW version

•Play in class with the normal version

Download: PDF of questions and answers

Piaget and Cognitive Development

Play alone with the PREVIEW version

Play in class with the normal version

Buzz Words 2

Play alone with the preview version

Play in class with the normal version

Intelligence, IQ, Theorists and Problems

Intelligence, IQ, Theorists and Problems

Play alone with the preview version

Play in class with the normal version

Research Methods for Year 11 Psychology

Play alone with the preview version

VCE Psychology 2015 – Unit 2